A Simple Spit Test for Better Predictability of Duration of Concussions

Ready for a gross fact? On average, your salivary glands produce one to two liters of spit per day. Our teeth are basically swimming in the stuff, but for the most part, we don’t pay attention to saliva unless it’s flying out of someone’s mouth. And that’s too bad. Sure, spit is disgusting, but it’s really one of the fascinating fluids on the planet in addition to being equally important.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, noncoding molecules that influence protein translation throughout the body. They are transported through the extracellular space protected in exosomes and microvesicles, which allows them to be easily measured in biofluids, including serum, cerebrospinal fluid, and saliva. Because of their abundance, stability in fluctuating pH levels, resistance to enzymatic degradation, and essential role in transcriptional regulation, miRNAs make ideal biomarkers.

As mentioned earlier, spit/saliva is a very important body fluid. And now, diagnosing the severity of a concussion could soon be as simple as collecting a swab of saliva.

Yes, diagnosing a concussion can sometimes be a guessing game, but clues taken from small molecules in saliva may be able to help diagnose and predict the duration of

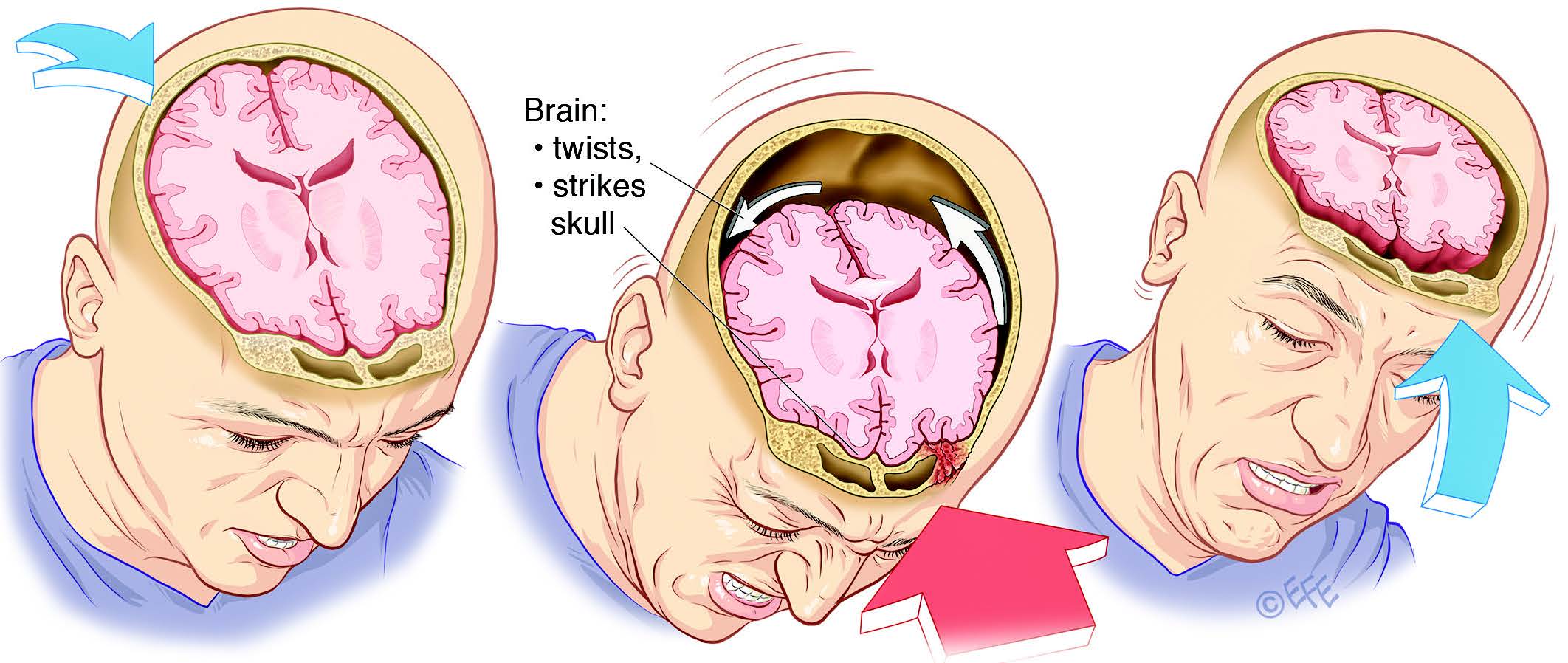

concussions in children, according to Penn State College of Medicine researchers.A concussion is one type of traumatic brain injury caused by a bump, blow or jolt to either the head or the body. Though not life-threatening, these injuries to the brain can be serious and cause symptoms of headache (or “pressure” in the head), nausea, vomiting, dizziness, balance problems, double or blurry vision, sluggishness, confusion, memory problems and difficulty concentrating.

In their study, Penn State College of Medicine researchers found microRNAs in saliva with real potential for identifying concussive symptoms in children, teens and young adults.

In 2013, there were about 2.8 million traumatic brain injury-related ER visits, hospitalizations and deaths in the US, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Steve Hicks, senior author of the study and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Penn State College of Medicine, said the “five microRNAs in saliva could predict with approximately 85% accuracy which concussed children would have symptoms one month later. In comparison, standard survey measures that are typically used in clinics were approximately 65% accurate.”

Nearly two-thirds of concussions take place in children and teens, Hicks and his co-authors noted. Although most patients’ symptoms disappear within two weeks, one-third of children and teens may experience prolonged symptoms of concussion.

“It’s frustrating for both parents and physicians that we can’t accurately and objectively predict how long a child’s concussion symptoms might last, what those symptoms are likely to consist of and when it might be safe for them to return to sports or school,” said Hicks.

The researchers recruited 52 concussion patients between the ages of 7 and 21 for the study. Each participant was evaluated using the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT-3)- a common tool that doctors use to inventory concussion symptoms and severity- within two weeks of their injury. The researchers also asked the patients’ parents for their observations about their children’s symptoms. This assessment was repeated four weeks after the injury occurred.

In the study, the researchers also collected saliva from each participant and analyzed for levels of different microRNAs. They then compared the microRNA profiles to the patient’s symptoms at both the initial and follow-up assessments.

The researchers isolated five microRNAs that could accurately identify the participants who would experience prolonged symptoms. These microRNAs could correctly identify if a participant would have prolonged symptoms or not for 42 of 50 participants.

“The miRNAs associated with prolonged concussion symptoms have potential utility as a toolset for facilitating concussion management. This tool could ease parental anxiety about expected symptom duration. An objective prolonged concussion symptoms tool could also inform clinical recommendations about return-to-play and school-based accommodations,” the authors wrote.

Researchers did note that some patients used anti-inflammatory medicine, which could have altered their findings. They also acknowledged the size of the study, explaining that a larger cohort would be needed to verify conclusions.

“The ultimate goal is to be able to objectively identify that a concussion has happened and then predict how long the symptoms will go on for,” Hicks said. “Then we can use that knowledge to improve the care that we provide for children who have concussions, either by starting medicine earlier or holding them out of activities for longer.”

In addition, some scientists are exploring functional MRI techniques to look at the metabolic function of different areas of the brain to gain insight into concussion, he said.

Hicks said he and his colleagues are collaborating with others to examine saliva biomarkers in adult athletes and members of the armed services. “Because the markers we identified in this study are not correlated with patient age, we are hopeful they may be applied in adult populations, as well,” he said.